On July 16, 2020, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) struck down the Privacy Shield, the adequacy agreement securing personal data transfers between the United States and the European Union (EU). In the absence of an adequacy decision, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) requires enhanced security for data transfers outside the European Economic Area (EEA).

Thus, for almost two years, companies have had to implement sometimes complex legal, technical and organisational measures to continue using foreign technological solutions, particularly from the United States.

Nevertheless, recent decisions on the use of Google Analytics demonstrate that these measures are actually not sufficient to ensure compliance with the GDPR. In this context, the announcement of a new agreement in principle between the EU and the US is welcomed with relief by the organisations concerned. However, some scepticism remains as to the effectiveness and even the durability of the future system.

Personal data transfers: an ill-defined concept

As surprising as it may seem, the notion of transfer is not clearly defined by the GDPR. For the CNIL, there is a transfer as soon as there is a “communication, copy or movement of personal data”. This broad definition includes a wide range of activities, from storage to simple consultation, which then constitutes processing within the meaning of the GDPR and implies compliance with its provisions.

Among these transfer activities, a distinction is made between data transfers to a recipient outside the European Economic Area (EEA), which are known as cross-border transfers.

Cross-border transfers are an everyday occurrence and essential to both trade and international cooperation. Yet, on a global scale, the inequalities in privacy protection, and the differences in priorities as to its balance with public security, present a definite risk to the rights and freedoms of individuals. It is precisely for this reason that cross-border transfers are subject to special attention, the regime of which is governed by the provisions of Chapter V of the GDPR.

It requires the Data Controller (DC) and any Subcontractors (SC) to ensure that the level of protection of individuals is not compromised during a transfer to a third party located outside the EEA, which implies a comparison between the guarantees of the GDPR and those offered by the legislation of the third country of destination. Faced with this guiding principle, three situations are envisioned:

- When the recipient country has a legal and institutional framework capable of ensuring a level of protection equivalent to that of the GDPR, this situation is established by the European Commission through an adequacy decision. From then on, any transfer to an adequate country (there are 14 of them to date) is authorised in principle.

- On the other hand, transfers to unsuitable countries must be carried out within a framework secured by appropriate measures likely to guarantee the respect of the rights and freedoms of the persons concerned.

- Finally, in certain exceptions provided for in Article 49 of the GDPR, the transfer may be authorised in a derogatory manner.

What are the transfer mechanisms in the absence of a matching decision?

To transfer personal data to an unsuitable country, there are two main transfer mechanisms:

- The adoption of Binding Corporate Rules (BCR) which allows groups operating on European soil to regulate data transfers between their entities internally;

- The signing of the European Commission’s Standard Contractual Clauses (SCC), which allows for the supervision of transfers between the exporter and the importer of data.

Despite the complexity and lack of flexibility of the STCs, a Digital Europe study conducted at the end of 2020 shows that this is the most common transfer mechanism in the private sector. In fact, out of 300 large and medium-sized companies consulted, 85% said they were concerned by CCTs.

A special case: data transfers to the United States

The United States, the EU’s largest economic and political partner, has always been treated differently. We should speak more accurately of adequacy agreements than of unilateral recognition of adequacy.

As early as 2000, even before the adoption of the GDPR, the first agreement, the Safe Harbour, authorised transfers of personal data between the EU and the United States.

The Safe Harbour held up until 2013. That’s when whistleblower Edward Snowden revealed that, based on the 1978 Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), the National Security Agency (NSA) was collecting personal data of Europeans en masse, for profiling purposes among others.

In addition to creating a climate of distrust among the general public, this scandal highlighted the inability of political agreements such as Safe Harbour to bridge the profound mismatch between the U.S. vision of national security and the European conception of privacy.

It was in a judgment of October 6, 2015, known as Schrems I (named after the Austrian whistleblower who initiated the appeal), that the CJEU finally invalidated Safe Harbour. At the time, it stated that “a regulation allowing public authorities general access to the content of electronic communications must be regarded as undermining the essential content of the fundamental right to respect for private life.”

Only four months later, the EU and the United States announced a new agreement governing transatlantic data transfers: the Privacy Shield. The adequacy decision endorsing this agreement followed in less than five months.

Again, Max Schrems challenged the agreement on similar grounds, and the Privacy Shield fell in turn in the ECJ’s “Schrems II” ruling of July 16, 2020. The United States found itself stripped of its adequacy decision for a second time.

In the following months, contrary to expectations, no new adequacy agreement was adopted. The organisations concerned were therefore obliged to regulate their treatment by means of other mechanisms.

The reinforcement of European requirements following the Schrems II ruling

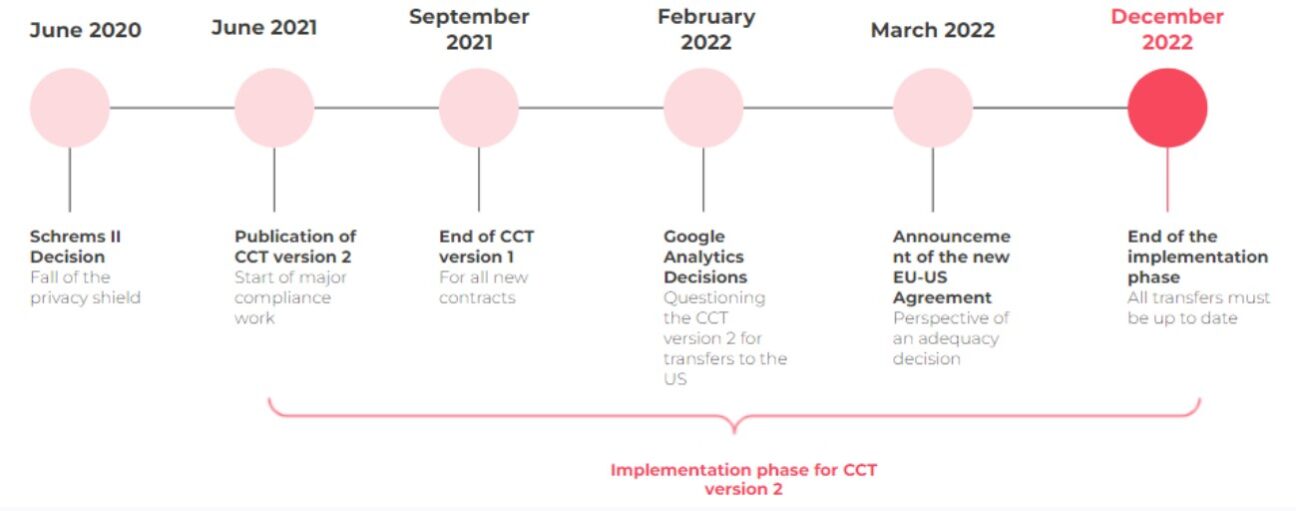

In June 2021, one year after the invalidation of the Privacy Shield, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) published its dedicated recommendations. Simultaneously, the European Commission adopted an updated version of the CCTs (version 2)2. This update of the CCTs comes with two implementation deadlines:

- 3 months, i.e., until September 27, 2021, to cease using the version 1 CCTs for new contracts;

- 18 months, or until December 27, 2022, to update the LAB in pre-existing contracts.

The adoption of CCT version 2 is a consequence of the Schrems II decision. However, their application is not limited to transfers to the United States: it calls into question transfers to all inappropriate countries.

Companies were therefore quickly confronted with a substantial task of updating their contracts. However, for the Commission, CTCs are not enough to ensure compliance with cross-border transfers. It also requires that these activities respect the recommendations of the EDPB, which tightens the rules on transfers.

Post-Schrems II transfers: a difficult compliance process

These new requirements seem to be out of step with the reality of the market. A quarter of companies are not aware of their data transfer activities and only 50% of companies, mostly large groups, declare that they have set up an action plan to respond to the consequences of the Schrems II ruling. The latter group has been facing difficulties on several levels for almost a year.

First, companies are facing organisational difficulties. Without specifying a methodology, the EDPB’s recommendations require an analysis of the level of security inherent in the planned cross-border transfer. To meet this requirement, we note that most organisations conduct transfer impact analyses (TIAs).

Furthermore, the GDPR places these requirements on the data exporter, regardless of whether they are an RT or ST. Yet, the GDPR does require the RT to be able to demonstrate the compliance of its processing, including transfers, and its chain of subcontractors. In practice, we note that many STs, even though they are exporters, are unaware – voluntarily or not – of their obligations with regard to the CCT version 2, and leave it to the RTs to carry out the TIA. This vagueness in both the method to be followed and the responsibility scheme greatly complicates the compliance of transfers.

Secondly, companies are encountering technical difficulties. According to the EDPB, if the analysis of the transfer reveals a certain risk for the data, then the RT and the ST must coordinate to implement technical and organisational measures (TOMs) to secure the transfers.

However, the digital giants leave very little room for customisation and negotiation with their customers. Many of them have limited themselves to publishing white papers on the so-called compliance of their security measures. This is accompanied by URL links to data protection clauses that they can unilaterally change and v2 TCCs that RTs must automatically adhere to.

It is important to recognise that in the case of US cloud solutions, since the data is necessarily stored in the clear (unencrypted) in the systems, there is currently no satisfactory measure to prevent access to the data by government authorities. This is however the very heart of the problem with regulations like FISA but also the Cloud Act of 2018.

Finally, the last major difficulty, an unforeseen consequence of the Schrems II ruling: the rebound effect. Indeed, in the case of the United States, the extraterritoriality of FISA and the Cloud Act implies that the European subsidiaries of American companies may be obliged to transmit personal data to their parent companies in clear text, even if the data is only stored and handled in Europe.

For almost a year, companies have been performing a real balancing act to navigate through these difficulties. It is in this climate of uncertainty, fatalism, and even wait-and-see attitude that the first Google Analytics decisions were made.

The collapse of the status quo following Google Analytics decisions

During 2021, None of your Business (NOYB), an association co-founded by Max Schrems, filed 101 complaints with several European supervisory authorities against websites using Google Analytics or Facebook Connect. This is what NOYB facetiously calls the “101 Dalmatians”.

In January 2022, the first sanction falls. The European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) sanctioned the European Parliament for its use of cookies on the website it had set up to allow its employees to register for COVID-19 tests.

In addition to a general argument about the lack of information to data subjects about the use of certain cookies, the EDPS criticises the European Parliament for the use of Google Analytics on the grounds that this involves the transfer of data to Google LLC in the United States. Consequently, these data are subject to the provisions of FISA and the Cloud Act and therefore nothing can prevent their disclosure to US intelligence services. The EDPS, therefore, put the Parliament on notice to stop this practice.

A week later, it was the turn of the Austrian supervisory authority (DSB) to issue a similar decision. The DSB underlines that even if the CCT v2 has been implemented, a TIA has been carried out and additional TOMs have been adopted, the use of Google Analytics is still illegal under the GDPR.

Then, last February, the French supervisory authority (CNIL) issued its own decision. It analysed each of the additional measures put in place by the RT and Google and concluded that none of them was sufficient to guarantee that the data would not be provided to US authorities and intelligence services. It confirms that this only possibility is contrary to Article 44 and following of the GDPR. Like the EDPS and the DSB before it, the CNIL does not impose a financial penalty but issues a formal notice.

Google Analytics, the latest twist: a risk-based approach to transfers would violate the GDPR

In response to these recent rulings, Google has introduced a new version of Google Analytics which is claimed to be compliant as it anonymises the IP addresses collected. Again, in April this year, the DSB declared the tool unlawful, notably on the grounds that IP anonymisation only takes place after the data has been collected.

More worryingly, the DSB rejected Google’s argument based on a risk-based approach. The authority states that the legality of a transfer (and therefore the possibility of proceeding or not) does not depend on the level of risk, the volume or the sensitivity of the data.

Given the number of pending referrals throughout the EU and the alignment of the 27 supervisory authorities in a task force on the subject, there is no doubt that other similar decisions will follow, possibly more severe with the imposition of financial penalties.

In the various sectors, while the Schrems II decision was sometimes treated lightly, we are now seeing a real awareness of the problems associated with data transfers to the United States. Panic is setting in. Many web hosts are abandoning Google Analytics in the wake of the decision or are preparing to do so. Companies are starting to map out their tools using Google’s solution in order to consider European alternatives, and to be able to make comparisons and cost estimates.

The prospect of a new agreement

Last March, the European Commission and the White House jointly announced that they had reached an agreement in principle on a new bilateral framework for data transfers between the EU and the US.

To date, no draft of this agreement has been published. Agreements in principle usually take 2-4 months to be translated into a legal text. The announcement does, however, hint at some of the broad outlines of the agreement that seek to directly address the reasons that led to the cancellation of the Privacy Shield.

The United States has thus committed to reforming its personal data protection regime in the specific context of intelligence activities. In particular, these activities will have to take into account the principles of necessity and proportionality in the context of requests for access to personal data for national security reasons. In addition, the United States has committed to establishing a two-tiered redress mechanism and to providing clear and transparent information on its intelligence activities.

Finally, the Commission and the White House talked about establishing an independent court that will have jurisdiction to handle complaints from individuals affected by a transfer of their data to the United States and a request for access from U.S. government agencies or intelligence services.

Another disappointment or final act?

These commitments provoke two types of reactions:

- The optimists see it as a quick and certain securing of their transfer activities to the United States. But this announcement does not mitigate their regrets regarding the investments and work undertaken as a result of the Schrems II decision.

- Some less optimistic organisations point out that this new adequacy agreement only concerns the United States and will therefore not change the new doctrine adopted with regard to transfers to unsuitable countries (and in particular, it should be remembered, in the case of subsequent transfers). In addition, the time needed to translate the agreement into legal provisions still leaves some doubt as to the use of tools such as Google Analytics or reCAPTCHA.

The particular context of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict

Finally, it is worth recalling the particular context in which this agreement was announced. It was concluded at the same time as another transatlantic agreement, the one on the supply of gas by the United States to the EU in response to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict and the ensuing natural gas shortages.

For two years, the European executive and judicial bodies have been adamant that the Cloud Act and FISA compete with the principles of the GDPR. The acceptance of this agreement in principle is therefore questionable, even though the United States maintains its position that a No-Spy Act is unthinkable. In other words, there is no way to prevent the US intelligence services from requesting access to European data.

It should be remembered that transfers of personal data to the United States result in an economy that represents nearly 1,000 billion euros for the United States.

This new transatlantic agreement on data protection, therefore, appears to be a simple bargaining chip that the United States has imposed for its cooperation with the agreement on natural gas supply.

Yet another political agreement destined to disappear?

Like Safe Harbour and Privacy Shield, the new transatlantic agreement seems to be just another political agreement. And it is hard to imagine how, without the No-Spy Act, this agreement could meet the requirements of the CJEU and the supervisory authorities.

In a statement on this new agreement3, the EDPB has already expressed reservations. In addition, the CJEU also states that it is prepared to assess the compliance of this new agreement if the matter is referred to it.

It may not have to wait long for this to happen, as Max Schrems has already stated that the NOYB association is eagerly awaiting the draft of the agreement, which its experts will study in detail.

It is therefore likely that this agreement is just a Privacy Shield 2.0 that will disappear in its turn. We are far from the permanent adequacy decision so much expected by the actors of the privacy sector.

The danger of waiting for the agreement

Under these conditions, it is crucial not to relax compliance efforts through the implementation of TCC version 2. Not only will these continue to apply for destinations other than the U.S., but they are also an opportunity to strengthen its privacy-by-design processes and greatly improve its security resiliency.

Adequacy decision or not, we can no longer remain blind to the risks that US legislation poses to privacy. A feeling shared by the European authorities who have seized the opportunity to try to strengthen the regulation of the digital sector.

Devoteam’s Cybersecurity team is ready to help you take into account all your scenarios.

To learn more about how we can help you in the compliance of your organisations, contact our compliance experts.

1 https://www.digitaleurope.org/resources/schrems-ii-impact-survey-report/

2 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dec_impl/2021/914/oj?uri=CELEX:32021D0914&locale=fr

3 https://www.cnil.fr/sites/default/files/atoms/files/declaration_01-2022_du_cedpb_sur_lannonce_dun_accord_de_principe_sur_un_nouveau_cadre_transatlantique_pour_la_protection_des_donnees.pdf